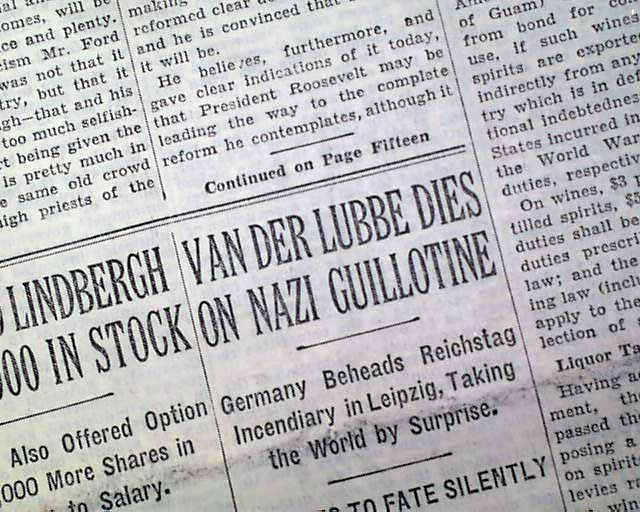

On February 27, 1933, the Reichstag (the parliament building) in Berlin, Germany, caught fire. A suspect, Marinus van der Lubbe, soon confessed, and portrayed himself as a lone-wolf arsonist. But Hitler had only just become Chancellor, and the fire gave him an opportunity to consolidate his power – he saw a broad Communist plot behind van der Lubbe, and soon prevailed upon President Paul von Hindenburg to suspend civil liberties to allow for the “ruthless confrontation” with that conspiracy.

From the start, many anti-Nazis agreed with Hitler that van

der Lubbe was merely a cog. On their account, the Hitler and his henchmen

themselves had been the malefactors.

Since the end of the Second World War, the hypotheses of the

lone-wolf arsonist and of the Nazi conspiracy have vied for dominance. Defenders of the lone-wolf view need not harbor any Nazi or neo-Nazi sympathies: distinguished historians like

Hans Mommsen, Ian Kershaw, and A.J.P. Taylor have taken that

view, seeing the fire as a matter of simple good luck for Hitler, and

accordingly bad luck for humanity.

But the author of a new book looking afresh at the whole question, Benjamin Carter Hett, doesn't see this as a matter of luck. He

maintains that Hitler made his own ‘luck.’

He also goes beyond the whodunit question, reviewing the

post-war debate of the 1950s and ‘60s especially, and putting that into

context. There was a mid-century current of opinion to the effect that human history

was mostly a matter of “accident and blunder” as Hett puts it. That was

Taylor’s view, for example. The ‘lone nut’ theory, combined with the fire’s

importance in cementing Nazi dictatorship, fit that premise nicely.

Comments

Post a Comment