On Wednesday, Britain's Chancellor of the Exchequer delivered what is known as the "Autumn statement" to the House of Commons. This is one of two economics-forecast statements each year.

It was much anticipated. Parliament wanted to know what the government knows, or believes, about the consequences of Brexit.

The Chancellor, and those who work under him at the Office for Budget Responsibility, haven't given many hostages to fortune in their statements, though. They assume that the UK will leave the European Union in April 2019. They guesstimate that the purely administrative costs of departure will amount to GB₤412 million (around US$511 million).

But on the critical issue of "passporting," they don't take a view. That is: in a "soft Brexit" scenario the banks headquartered in London will be able to negotiate for themselves or with the help of their government "passports" with the EU or constituent nations that will allow them to continue business-as-usual throughout Europe. In a "hard Brexit" scenario passports will be expensive, or unavailable and doing business on the other side of the channel will itself become a good deal trickier. The Exchequer and its OBR have no view on this. "We've not attempted to predict end point of the negotiations."

There will be no shrinkage of imports or exports across the Channel, although growth will slow.

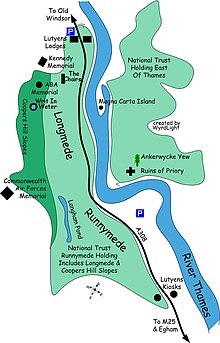

But the most fascinating tidbit to come out of the coverage of the Autumn Statement was the simple fact that the Chancellor, Philip Hammond, is member of parliament for Runnymede. Yes, Runnymede! Where the Magna Carta was signed. What a great spot of world-historical real estate!

Comments

Post a Comment