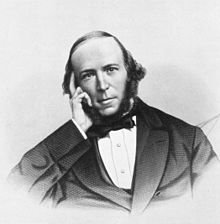

Herbert Spencer is often called a “Social Darwinist.” I have called him that myself, and will probably do so often in the future as well, because that has become the traditional term and it is sometimes necessary to abide by conventions in order to make oneself understood.

But I have come to believe that the term is inapt. Two other labels suggest themselves as superior. If one is looking for a label Spencer would accept for his own social/ethical views, the term "rational utilitarianism" would work. If one doesn't care to ask his permission, social Lamarckianism will also apply.

Spencer's works on relevant subjects include SOCIAL STATICS (1851), THE STUDY OF SOCIOLOGY (1873), and MAN VERSUS THE STATE (1884).

Spencer called his own view “rational utilitarianism,” because -- as one might guess -- he believed utilitarians before him had been inadequately rational. He did identify the good with happiness, and that identification was associated for him with a belief that all creatures naturally seek preservation and reproduction, and that our sense of what makes us happy is biologically determined to direct us to serving those ends.

Since humans are rational animals, we engage in practical reasoning, figuring out how to make ourselves happy and live with each other through certain rules of thumb that become common sense over time. This impetus leads us toward contract and away from status — it leads us to pay less attention generation by generation to the station into which we were born or that in which the fellow next to us was born, and more attention to what we can give to and get from one another via voluntary agreements. Further (since Spencer was as I noted a Lamarckian) he believed that these commonsense rules were not only culturally heritable, they were even genetically heritable, If I have figured out that contract is preferable to status, my kids will probably understand that more easily than I did, and their kids more easily still.

You may properly consider this a derivation of ethics (those commonsense principles we have all learned over time) from the implicit order found in nature (the environment that makes their exercise successful).

If I have reconstructed his thought accurately (I will refrain from recounting the scholarly debates on the subject over the last 150 years or so), this is an internally plausible body of thought. I stress the adverb "internally." Factors external to the body of thought have rendered it implausible. Lamarckianism has fallen into disrepute, for one thing. More so: In light of 21st century biology, any idea that evolution, whatever exactly its mechanism, contributes to such cognitive specifics as a recognition of the value of contracts, or even the value of keeping one's promises, seems absurd.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes cites Spencer's SOCIAL STATICS in his dissent in Lochner v. New York (1905): "The Fourteenth Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer's Social Statics." Holmes was dissenting from the Court's finding a right to contract in the U.S. Constitution, which rendered unconstitutional a state law limiting the number of hours that a bakery could require its employees to work.

ReplyDeleteTrue. One odd thing about that: SOCIAL STATICS was far from the most germane of Spencer's books for that proposition. Either of the other two I mentioned would have been more germane. SOCIAL STATICS was a work of Spencer's wild long-haired youth, and it attracted favorable attention from such as Leo Tolstoy for its treatment if the "Land Question," its anti-landlord sentiments. One might imagine one of the members of the Lochner majority muttering "we sure as heck don't mean to incorporate THAT Spencer, anyway." But some suspect that notorious comment was a bit of a personal joke on Holmes' part, confident that the members of the majority wouldn't pick up on it because they didn't read that sort of book.

ReplyDelete"of the 'Land Question'" I meant.

ReplyDelete