Unless memory fails me, we have never before discussed on this blog the crash of something-or-other at a ranch near Roswell, New Mexico on July 7, 1947.

I bring it up now only to say that Roswell, and the much-discussed theory that the crash was of an alien flying saucer, makes a brief appearance in the recent book by Guy Lawson: Octopus: Sam Israel, the Secret Market, and Wall Street's Wildest Con.

The gist of Lawson's book is difficult to explain, but I'll dive in anyway. Sam Israel was one of the three principals of a high-flying hedge fund in the early years of the 21st century, a hedge fund called Bayou Capital, though it was run out of Fairfield County, Connecticut. It was called Bayou in recognition of Israel's renown Louisianan family.

In 2005, CNN Money described Bayou's collapse as "one of the most bizarre hedge fund blowups in recent years."

But they didn't know the half of it.

What Lawson focuses on is the strange confidence that prevailed in the final months of Bayou's existence. The fund wasn't making anything like the returns it was claiming, yet for a long time Israel was eerily confident everything would work out. He could get money from European sources, make up the shortfall, and all would be well.

He had confidence in those European sources because he was himself as much the victim as the perpetrator of a con. And the con man who was taking him for a ride, instilling him with that false confidence, was a fellow called Robert Booth Nichols.

Nichols had the air of a man who knew many mysteries, but who didn't want to reveal them to his good friends like Israel because ignorance is safer. But he could allow himself to be talked into disclosures, about a "secret market" where only the richest 13 families in the world and their good friends trade, about the extraordinary measures these 13 families go to, to maintain their control over the world, about how all the usual wacko conspiracy theories are true, but all of them are understatements.

The European sources of the money were to some degree Nichols confederates in bilking Israel. To a degree they were self-deluded, and bilking themselves as much as anyone else.

There are two possible reactions one can have if one is told that there are 13 families controlling the world and that everything we think we now about the world is a show these 13 families put on for our benefit. I mean, assuming you believe it. Reaction One -- let us, the masses, the non-privileged, rise up against them and take back the planet! The usual crowd of purveyors of conspiracy theory are promoting just that response.

But the other possible reaction is: hey, wouldn't it be cool if I could become their friend? if I could trade on favorable terms in the secret markets, with the prime banks, that the elite have created for themselves? This is the reaction Israel had -- the reaction he had to have, as Bayou circled the drain, the reaction on which Nichols counted.

At any rate, at one point Nichols is trying to persuade Israel and Bayou's CFO, Dan Marino (not the football player!), to wire $138 million from an account Bayou had with Citicorp to a German bank. This payment was all part of the big picture of getting in good with the 13 families, of course, and it would more than pay for itself in short order!

To their credit, executives of Citicorp asked sensible questions and held up this transfer.

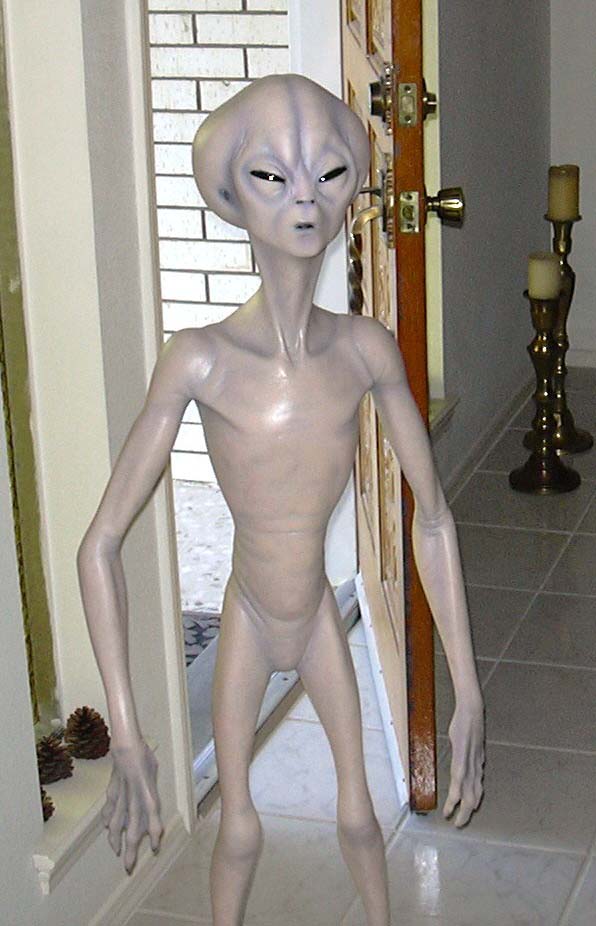

During a period when Israel had convinced himself that the Citicorp reluctance was a temporary glitch, he and Nichols had plenty of opportunities for heart-to-heart talks about how the world really works, and it this context Nichols told Israel that an alien really had landed at Roswell. But it had died while in captivity: because it turns out aliens are allergic to strawberry ice cream.

And even that tale didn't persuade Israel that Nichols was bad news?

Comments

Post a Comment