On a message board site, someone asked me recently what I understand by the phrase "religious freedom." I began my answer with words from Thomas Jefferson, but soon incorporated them into something broader, and something that may hold some interest for you, dear blog reader.

On a message board site, someone asked me recently what I understand by the phrase "religious freedom." I began my answer with words from Thomas Jefferson, but soon incorporated them into something broader, and something that may hold some interest for you, dear blog reader.I have three thoughts on the subject.

First, that my neighbor's belief that there is no God, or that there is one God, or that there are a thousand gods, in no case picks my pocket or breaks my bones. It in no case gives me a grievance against that neighbor.

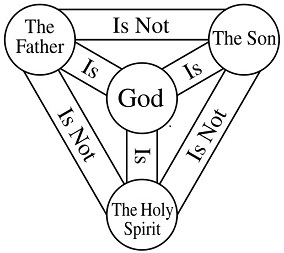

Secondly, that I should consider in the same spirit my neighbor's belief that there is one God who is Three Persons. Suppose I believe that to be logically incoherent and obscurantist. Or ... suppose I believe it to be right, but also believe that my neighbor misunderstands this Trinitarian idea completely. Again, in no case does that give me a grievance against my neighbor.

Thirdly, my thought is that there is no obligation to keep these beliefs pent up inside, hidden from the world. My neighbor's proclamation of his beliefs, in words or in the practical and/or symbolic ways that his tradition entails, [such as, for example, keeping his children out of state-sponsored educational institutions] gives me no grievance against him. ["That offends me" is not the statement of a grievance.]

Where there is a state/government, "religious freedom" means that the state/government acts in accord with the above negations. It will not support, either practically or symbolically, anyone's sense of grievance or offense against his neighbor's beliefs.

When there is no state, when the anarcho-capitalist community exists, "religious freedom" will be a matter of broad community assent to those propositions, and the resultant absence of any market demand for the silencing of any one's belief.

The First Amendment states, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. ..." ("Congress" should be read to refer to any branch of federal, state, or local government, down to public schools.) Your post, in effect, addresses the Free Exercise Clause but not the Establishment Clause.

ReplyDeleteSpecifically, if our "neighbor" is a state/government, do we have a grievance against it for expressing its religious beliefs, as when it puts "In God We Trust" on coins, when it adds "under God" to the Pledge of Allegiance, and when it opens Congress with a prayer?

Another question under the Establishment Clause is whether we have a grievance when the state/government spends our money to express its religious beliefs, or spends our money to allow others to express their religious beliefs, as when it pays for textbooks that teach creationism.

Finally, do we have a grievance when the state/government makes us a captive audience for its expression of its religious beliefs or others' expressions of their religious beliefs? That is what it does when it allows the teaching of creationism in public schools. The Supreme Court has held that this violates the Establishment Clause, but it has become a widespread practice in some states.

Henry,

ReplyDeleteYes, this was in constitutional terms a free-exercise kind of post, not an establishment clause kind of post.

I don't believe there are any good answers to the establishment clause questions, because given the background assumptions (that there will continue to be national sovereigns, for example, and that these sovereigns will continue to have some control over their nation's money supply) it is inevitable that they will take actions that many people will regard, reasonably, as an establishment of religion. Sovereigns are, after all, little gods on earth. And in the US public buildings, including the Supreme Court building, are typically designed to look like ancient Greek temples!

Sovereigns always look for legitimating ritual, to distinguish themselves from any private-sector band of robbers. "We're different from Tony Soprano, because we mint coins" doesn't sound as persuasive as if the coins themselves acknowledge a Higher Authority.

Christopher,

ReplyDeleteI hadn't thought of that -- that establishments of religion are a legitimating ritual. But I think that that may be more the case in dictatorships, where the individual dictator attempts to legitimate his personal rule by equating himself with a god. In the U.S., it seems to be taken for granted that the government is legitimate, and politicians establish religion more as a way to pander for votes.

But things may be changing in the U.S., as Bush v. Gore, Citizens United, gerrymandering, filibustering, and the 1% running things while most other people become worse off economically, diminish the belief that the government is democratic. If so, we may see more establishments of religion, for the reason you state.