I've discussed trolley problems before. This is a new version, in a new philosophical context.

One common issue in the philosophy of religion is: does religious belief help people act morally? If so, how?

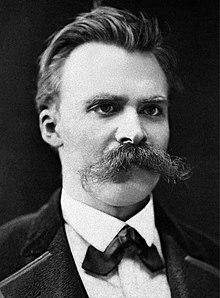

Nietzsche famously contended that the "death of God" had great implications for morality, for the transvaluation of values, implications which he welcomed. Many theists accept that judgment, but dis-value what Nietzsche valued. Many atheists and agnostics deny that there is any such implication.

One interpretation of Nietzsche's somewhat cryptic comments on the subject is that the idea of equality -- that my life is worth as much as yours, or in a variant that no quantitative comparison can or should be made between my life's value and yours -- is a religious presumption at heart. It depends upon the background notion that we are all alike creatures of the same Creator and it will not long outlast the death of that idea.

In that spirit, Brian Leiter has recently written a paper on the connection of ideas in Nietzsche's work. You can download it via SSRN. Or read a précis on his blog at typepad.

Here's what may be the money quote (taken from that blog):

Consider the Nietzschean Trolley Problem (apologies for anachronism): a runaway trolley is hurtling down the tracks towards Beethoven, before he has even written the Eroica symphony; by throwing a switch, you can divert the trolley so that it runs down five (or fifty) ordinary people, non-entities (say university professors of law or philosophy) of various stripes (“herd animals” in Nietzschean lingo), and Beethoven is saved. For the anti-egalitarian, this problem is not a problem: one should of course save a human genius at the expense of many mediocrities. To reason that way is, of course, to repudiate moral egalitarianism. Belief in an egalitarian God would thwart that line of reasoning; but absent that belief, what would?

Comments

Post a Comment