Certainly it is easy to create a literary aesthetics of brevity. The haiku and the aphorism have their admirers.

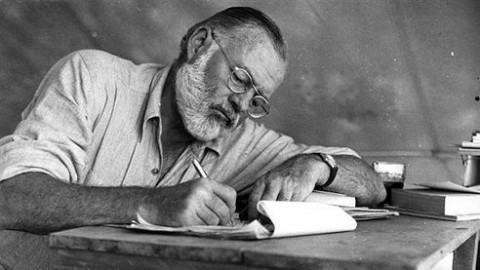

Ernest Hemingway is widely thought to have invented a perfect short story in the form of a classified ad: "For sale, baby shoes, never used."

Edgar Allen Poe famously developed a theory for why short stories are superior to novels. His explanation of that theory was, IMHO, longer winded than it had to be. The point, though, was that a story should have a unitary impact and this could be achieved best with a work that could be read in a single sitting.

Yet one shouldn't let the aesthetics of the short haul have the last word. The world has room for Melville's and Tolstoy's and Victor Hugo's novels, and creating a Reader's Digest version thereof will never be the same.

As for Hemingway's six word story? He didn't really write it. It is the work of a playwright named John deGroot who created a one-actor play about "Papa" in the 1990s.

Still, that six-word story works. How? It works on a meta level by inspiring us to do the first level narrative work ourselves. We imagine a loving couple expecting a baby, shopping for what the baby would need, including of course a pair of perfect shoes. Gazing fondly at those shoes day after day and anticipating the feet that would fill them. Then, tragedy, miscarriage, grief. We fill it all in and it ends with the posting of that classified.

Part of the secret of concision, then, is authorial laziness.

As for this blog entry? It is a good deal longer than 6 words but shorter than deGroot's play, and a lot shorter than For Whom the Bell Tolls. Which tells you nothing at all about its literary value.

Comments

Post a Comment