In 1823, the five great powers of the continent of Europe were scheming to reverse an outbreak of revolutions in South America. There powers were: France, Spain, Russia, Austria, and Prussia. This was the situation that created the Monroe Doctrine.

Great Britain's elite was unhappy about the counter-revolutionary scheming: not because it was sentimental about the national sovereignty of the new powers an ocean away, but chiefly because Great Britain's interests as a hegemon were threatened by any cause that promoted unity among those older powers on a continent so close its best swimmers could get there without mechanical help.

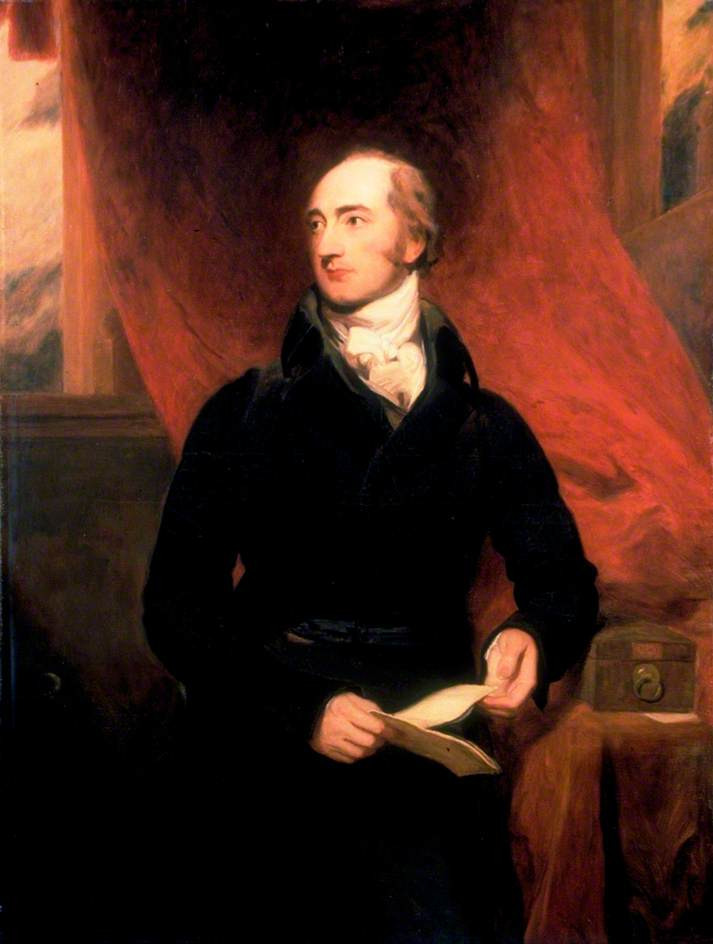

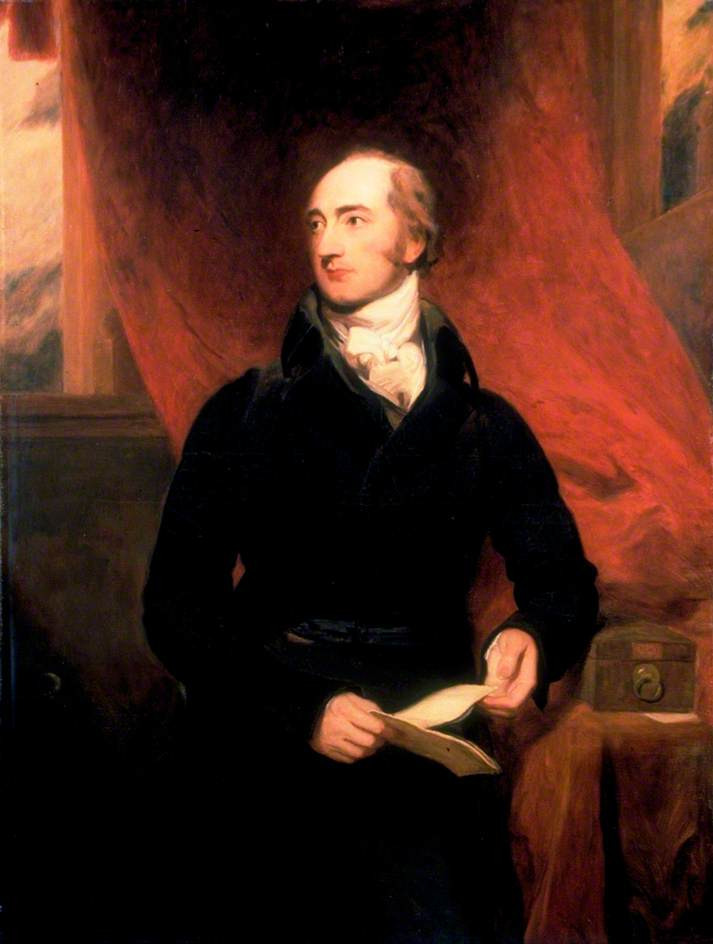

The Prime Minister of Britain was George Canning (pictured above). He proposed to Monroe's administration that it join with Britain in a warning to those five continental powers about the errors of their colonialism-reasserting ways.

Much of Monroe's cabinet thought this was a good idea. It was Secretary of State John Quincy Adams who argued forcefully against it, saying: "It would be more candid, as well as more dignified, to avow our principles explicitly" rather than coming into the discussion "as a cockboat in the wake of the British man-of-war."

Q won his point, which is why we have a Monroe doctrine rather than a codicil to Canning.

This has been your random historical observation for the day.

Great Britain's elite was unhappy about the counter-revolutionary scheming: not because it was sentimental about the national sovereignty of the new powers an ocean away, but chiefly because Great Britain's interests as a hegemon were threatened by any cause that promoted unity among those older powers on a continent so close its best swimmers could get there without mechanical help.

The Prime Minister of Britain was George Canning (pictured above). He proposed to Monroe's administration that it join with Britain in a warning to those five continental powers about the errors of their colonialism-reasserting ways.

Much of Monroe's cabinet thought this was a good idea. It was Secretary of State John Quincy Adams who argued forcefully against it, saying: "It would be more candid, as well as more dignified, to avow our principles explicitly" rather than coming into the discussion "as a cockboat in the wake of the British man-of-war."

Q won his point, which is why we have a Monroe doctrine rather than a codicil to Canning.

This has been your random historical observation for the day.

Comments

Post a Comment