So: what is the philosophical significance of the Kant-Laplace hypothesis, otherwise known as the "nebular hypothesis," which nowadays rules the roost of origin-of-solar-system views?

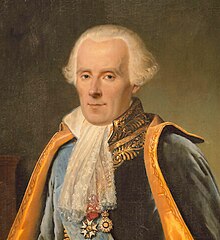

In chronology, by the way, Kant was way ahead of Laplace, although Laplace gets his name on the theory due to his more analytical, mathematical treatment of the subject. And I've just put Laplace's picture in here.

Now, is there any worthwhile connection we may draw between Kant the astronomer and Kant the philosopher? I think there is.

The nebular hypothesis is a blow (how serious a blow I leave to the reader's own intuition, but surely some sort of a blow) to the single most psychologically powerful argument for the existence of a Providential, supernatural Being -- the argument from design. After all, the solar system, with its marvellous equilibrium and its subtle but overwhelming predictability, is Exhibit A for the designedness of the universe, is it not? Yet Kant's work shows how the development of this solar system can be explained in a purely materialistic/mechanistic way, without any teleology, although given certain initial conditions.

Many years later, after expounding this theory, Kant wrote his famous "Critiques," reworking epistemology, ethics, aesthetics and, not to be overlooked, the philosophy of religion. What did Kant say as to the last of those? He said that none of the proposed proofs of the existence of God can persuade, but that this shouldn't be an obstruction for Faith.

After all, the really real, the noumenal world, is unknowable. And if a Providential, supernatural Being Exists at all, that Being is surely noumenal. So ... the proofs ought to fail, and Faith ought to step into their place. I do sense a connection.

Perhaps it wasn't really David Hume who awoke Kant from his dogmatic slumber. Perhaps it was the younger Kant, and his work on the solar system.

Comments

Post a Comment