We discussed quantum theory yesterday. Now it is time to remind ourselves of the other half of our proposed mash-up. 'Bayesianism' is an approach to probability theory that begins with subjectivity, with somebody's guess about what is the likelihood of an event. It then discusses how an individual having certain circumstances may change his beliefs rationally, and (assuming he has beliefs on more than one question) may keep them consistent with one another -- or, in other words, how he may keep his view of the world coherent.

The chief rival of Bayesianism is "frequentism." This treats probability as an objective fact in the world, another name for the frequency of some outcomes vis-a-vis others.

I've discussed this difference before. But ... what does it have to do with quantum theory?

Collapse the Function for your own Damned Self

With a Bayesian approach we get a take on quantum theory that doesn't shrug its shoulders at the "what is really happening?" question in the way the Copenhagen interpretation does. On the other hand, it doesn't require those other worlds to allow is to make sense of this one, in the way the many-worlds interpretation does. Rather, the Bayesian approach accepts the limits of any inquirer's point of view, and makes those limits the key to understanding the apparently spooky stuff in quantum phenomena.

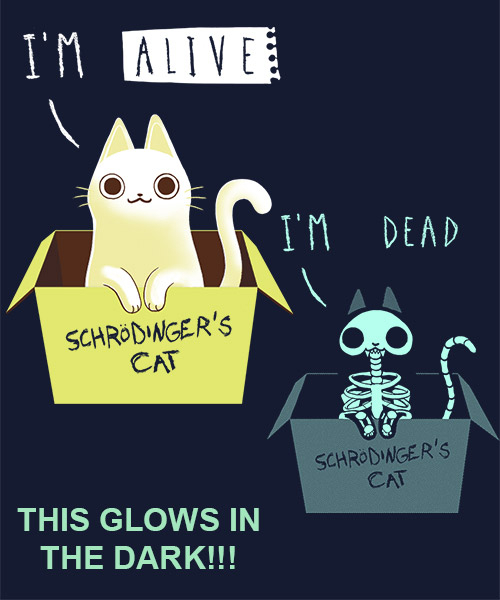

The cat? It just becomes a matter of a particular observer updating her beliefs after a new experience, the opening of the lid. The issue is how to change beliefs rationally, and how to keep one's beliefs coherent. The sight of a dead cat is pretty self-explanatory, so it shouldn't be surprising we re-work our view of what happened inside that box before that measurement, in its light. Most wave-function collapses can be understood in an analogous way without too much fuss once -- and without a living cat in a diverging world -- once we abandon the notion that we're looking for some ideally objective assessment of events.

Storytelling amidst Equations

We're looking, more modestly, to tell coherent stories about a world of which our own consciousness is a part.

Physics becomes, as physicist Christopher Fuchs puts it, "a dynamic interplay between storytelling and equation writing. Neither one stands alone, not even at the end of the day.”

What about the "action at a distance" question, aka quantum entanglement? How does BQ theory deal with this?

Let's review the problem. This is the stuff that really inspires New Agey understandings of the science. Think of two particles that have been "separated from birth." They are shot off in two very different directions. Eventually they are very far from one another -- one, say, is on Mars, the other on Earth. An experimenter on earth takes a measurement of the spin of particle A (from the original AB pair). In taking that measurement -- as the Copenhagen interpretation sees it -- that experimenter actually GIVES the particle a specific spin, which was indeterminate before. But (this is the weird part) he gives B the spin in question, too. Thus, "action at a distance," potentially communication between Earth and Mars faster than the speed of light and, perhaps, even Star Trek style teleportation. They may all come out of this preserved connection of A and B.

What does BQ have to say about this? I'll simply quote what Amanda Gefter, of QUANTA MAGAZINE, writes about this:

"Spooky action at a distance ... turns out not to be so spooky -- the measurement here simply provides information that the observer can use to bet on the state of the distant particle, should she come into contact with it." and as to the observer on Mars, "since the wavefunction doesn't belong to the system itself, each observer has her own, My wave function doesn't have to align with yours."

I'm not sure I fully understand this. I think it is saying that the observer on the Martian lab isn't seeing the "same" reality as the observer on earth. We each abide in our own world of probabilities, interacting with each other but never identical with each other. If I get it at all, I find it a more attractive way of dealing with the apparent spookiness than is the many-world's view so beloved of sci fi writers.

The scientists in the different labs might end up telling different stories, even at the "end of the day."

Aesthetic Appeal

Why this aesthetic appeal? Well, it isn;t' that I find the idea of multiple universes unappealing. In fact, I do find it appealing, but in a very different sense and cosmological context.

On the level of cosmology, I are sympathetic to the speculation that the collapse of a star into a black hole in one universe is the creation of another universe with its own space time and its own physical laws. Every black hole is a womb. THIS idea allows for the further thought that the steady-state theorists were right though a bit parochial. No particular universe is in a steady state. Perhaps each is born, expands indefinitely, and dies. Some of them in the process give rise to other universes. Perhaps the multiverse is in a steady state in some sense.

So I do believe in a sense, in multiple world lines. But I prefer to take my multiplicity from cosmology rather than from particle physics, thank you. I prefer not to mix things up unnecessarily with a multiplicity OF multiplicities.

So I'll let Bayesian probability handle the spookiness of quanta.

These thoughts constitute enough out-of-my-depth rumination for the day,

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete