And so the utmost a student of sociology can ever predict is that if a genius of a certain sort show the way, society will be sure to follow. It might long ago have been predicted with great confidence that both Italy and Germany would reach a stable unity if someone could but succeed in starting the process. It could not have been predicted, however, that the modus operandi in each case would be subordination to a paramount state rather than federation, because no historian could have calculated the freaks of birth and fortune which gave at the same moment such positions of authority to such peculiar individuals as Napoleon III, Bismarck, and Cavour.

William James, "Great Men and their Environment," 1880.

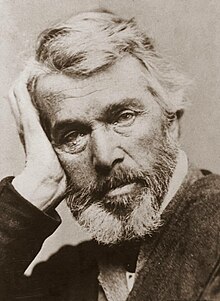

James was here rehabilitating something akin to the Carlylean theory of history as a set of the biographies of certain extraordinary individuals. Not exactly Carlylean -- there are important differences -- but this passage indicates the real similarity.

Napoleon III plays two roles in the above threesome. On the one hand, his policy as the French head of state was to assist the unification of Italy (for a price). Thus, he was allied with Cavour's Italian nationalism in the 1850s, and because Cavour was victorious France gained Savoy and the County of Nice.

But Napoleon III is also here (I think he was chiefly here) as an example of historic folly, and as a foil for Bismarck. In 1870 Napoleon entered into war with Prussia without adequate military forces (some of which he had wasted in an adventure in Mexico) and without allies. He was captured at the battle of Sedan, and his Empire was heard from nevermore.

Setting him aside, Cavour and Bismarck are the sort of individuals of whom Carlyle might have written.

Carlyle was, in fact, though past his prime, still alive when James first spoke the above italicized words. Carlyle had written his own work on "heroes" in history forty years before, and well before the unification of Italy or Germany of which James speaks here. He likely would have concurred with the above words, except that he might have thought them wussy -- hedged in a qualified in a way that a Great Man as Scholar should disdain.

Should any reader be unsure: I have illustrated this blog entry with a portrait of Carlyle, not of James.

Comments

Post a Comment