A complete list of the Rightward Shoves in US political presidential history, according to the cyclical theory I described recently.

John Adams elected 1796. One term.

28 years later....

John Quincy Adams, elected (by the House of Representatives) 1824. One term.

32 years later....

James Buchanan elected 1856. One term. Union dissolved on his watch.

Then history does a bit of a stutter step. A civil war and its aftermath messes up the cycles a bit. Grover Cleveland is elected for the first time in 1884, 28 years after Buchanan. On schedule if we consider that the shove. He is defeated in 1888 (due to electoral college arithmetic) and triumphantly re-elected for a non-consecutive term in 1892. The subsequent cycles work out properly if we count the second Cleveland victory as the shove.

So count both 1884 and 1892 as necessary.

28 years later after the latter....

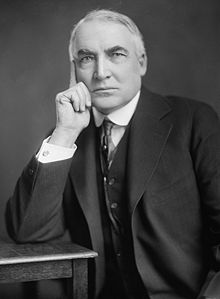

Warren G. Harding elected 1920. Dies in office. Portrayed above, he was the first of three Republicans.

32 years later....

Dwight D. Eisenhower elected 1952. First of two full terms.

28 years later....

Ronald Reagan elected 1980. First of two full terms.

36 years later....

Donald Trump elected 2016.

In what sense were the Adamses on the right? I know little about them, other than that they were the only Presidents among the first six who were not Southern slave holders.

ReplyDeleteSame question as to Buchanan: All I know about him is that, like his predecessor Franklin Pierce, he was a Northerner but sympathetic to slavery. So how did he move rightward?

At the time of the first Adams' election, France was the center or revolutionary activity in the world. Adams' foreign policy was Anglophilic, and to that extent revolution-containing. Jefferson of course would change this, and under Madison we'd essentially become military allies of the French in the final stages of the Napoleonic War, getting our capital city burnt in the process.

ReplyDeleteBy the second Adams' day, the breakdown of left/right by French-English sympathies is obsolete. But I think it fair to say that his supporters considered him a link back to the good ol' days, a barrier against dangerous Jacksonian trends such as suffrage for all white men regardless of wealth or its absence.

Buchanan was inaugurated at almost the same moment that the Supreme Court announced its Dred Scott decision, for which he was an enthusiast. IIRC, he made a statement during his inaugural address that indicated he knew how the forthcoming decision would go -- he was 'in on' the rightward shove the court was about to administer.

So let us try to generalize a bit. A leftward move has generally involving widening the circle of rights-bearing beings. More specifically, it has involved expansion the circle of suffrage-exercising beings (almost definitionally a smaller included circle). In foreign policy, this means allying one's country with other countries, or even with movements in other countries, that are seeking to do the same.

ReplyDeleteThe first Adams fits the rightward tag because of his foreign policy. The second Adams because he and his Whig party were comfortable with property qualifications for the franchise. The Dred Scott decision, and by extension Buchanan, because of its even then shocking pronouncement that even free blacks have no rights that any white man need respect -- a blunt narrowing of the wider of the two circles.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteCopyeditor! "A leftward move has generally INVOLVED a widening of the circle of rights-bearing beings.... expansion OF the circle of suffrage-exercising beings...."

ReplyDelete