[Despite my efforts to straighten things out, the fonts, spacing, etc, in this post has ended up an ugly hodge-podge. My apologies. - CF]

To first amendment lawyers, this is preeminently the term in which Matal v. Tam found that the disparagement clause of the trademark statute infringes upon the free speech right under the first amendment. The court was unanimous as to the judgment (that the "Slants," a dance-rock band, can be trademarked as such) though there were differences as to the reasoning.

Hugh C. Hansen, law professor at Fordham, has called this “one of the most important First Amendment free speech cases to come along in many years.”

To first amendment lawyers, this is preeminently the term in which Matal v. Tam found that the disparagement clause of the trademark statute infringes upon the free speech right under the first amendment. The court was unanimous as to the judgment (that the "Slants," a dance-rock band, can be trademarked as such) though there were differences as to the reasoning.

Hugh C. Hansen, law professor at Fordham, has called this “one of the most important First Amendment free speech cases to come along in many years.”

Simon Tam and his fellow band members made for sympathetic

defendants. They obviously were not disparaging their own Asian background.

They were appropriating a stereotypical slur concerning Asians’ eyes, in the

tradition of many groups throughout history who have turned insults into badges

of honor.

The Washington

Redskins are a less sympathetic litigant, though they surely will benefit.

Their trademark protection was cancelled three years ago on the basis of this

same disparagement clause. Since there is no special first amendment status for

irony, one can’t really give Tam a win without giving Redskins owner Daniel

Snyder a win.

The broader question is: where will the

constitutionalization of trademarks go from here? Are there other clauses of the underlying

statute that will come under assault? Almost certainly. Which assaults will

prevail? That’s trickier.

Gerrymandering

Cooper v. Harris concerns the equal protection clause

and racial gerrymandering. Gorsuch didn't take part. Kagan wrote for the court. 5-3 split with Thomas, perhaps unexpectedly, on

Kagan's side.

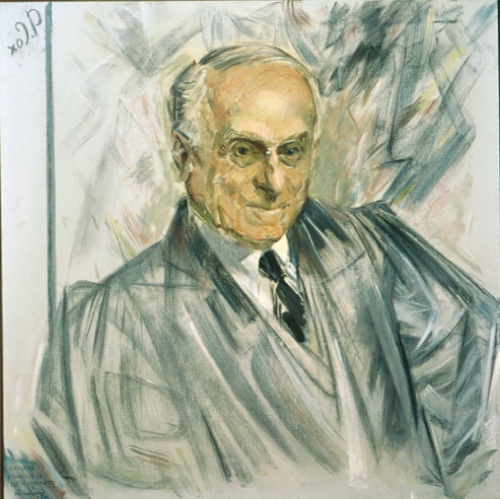

A long time ago the Supreme Court was

reluctant to enter the field of how state legislatures draw their congressional

districts. Justice Frankfurter (portrayed above) famously called the whole subject a

"political thicket." But the Warren Court, wielding the

"equal protection" clause, eventually entered that thicket, and

created a "one person one vote" rule. Actually, Warren and

Associates called it "one man, one vote," because you were still

allowed to use the word "man" generically without getting arrested in

those dark days.

Anyhoo ... SCOTUS has been

over-seeing lines in accord with this rule for decades now. Other principles

have entered into the picture too. Beyond one-person, one-vote, the court

has opposed "racial gerrymandering," the practice of drawing the

lines so that every person of a particular minority race ends up in the

same district, "bleaching" the neighboring districts, so to speak, in

the process.

SCOTUS has generally tried to stay out

of mere "partisan gerrymandering." A legislature of party

X can get away with drawing lines that advantage party X against party Y,

so long as there isn't much evidence they were thinking about race when they

did it.

In general, I suppose, in

the context of US law and politics, we can fairly use the term "left"

to refer to those who will in any particular situation favor closer monitoring

of those state legislatures to ensure the fairness of district lines, and the

term "right" to refer to those in any particular situation who say

that the state legislators should go about drawing the lines as they

think best. That's a

one-issue definition of those terms, and there will presumably be cases where

somebody "left" in other matters will be "right" on this

one and vice versa, but I think the labels are as fair here as they ever

are.

This week, on May 22, SCOTUS held for the plaintiffs in the case of COOPER v. HARRIS, striking down two congressional districts in North Carolina and sending the state legislators back to the drawing board. With regard to one of the two challenged districts the vote was unanimous (8 - 0 -- Gorsuch hadn't been on the bench when the matter was argued so he did not participate in deliberations.) With regard to the other challenged district, generally seen as the closer case, the vote was 5 - 3. Again, in favor of the plaintiffs and in favor of closer monitoring.

This week, on May 22, SCOTUS held for the plaintiffs in the case of COOPER v. HARRIS, striking down two congressional districts in North Carolina and sending the state legislators back to the drawing board. With regard to one of the two challenged districts the vote was unanimous (8 - 0 -- Gorsuch hadn't been on the bench when the matter was argued so he did not participate in deliberations.) With regard to the other challenged district, generally seen as the closer case, the vote was 5 - 3. Again, in favor of the plaintiffs and in favor of closer monitoring.

How did the Justices line up with

regard to District 12? Alito, Roberts, and Kennedy dissented. That is: they

said that striking down the district lines approved by the legislature was

unwise on the part of the court below, and they would have reversed that

decision. They also said the majority confused "a political

gerrymander for gerrymander for a racial gerrymander," etc.

So this was a standard left/right split

... right? Well, yes, except.

The majority consisted of Kagan (who

wrote the opinion), Sotomayor, Breyer, Ginsburg, and ... Clarence Thomas. There is some reason to hope that Thomas, freed from the influence of the dearly departed Justice Scalia, is now thinking for himself and will be an unreliable non-party-line sort of Justice for the remainder of his time on the bench.

One of Donald Trump's signature pledges as a candidate for President was to ban the entry into the United States of alien Muslims "until we can figure out what's going on." When he became President, this morphed into a halt on the entry of foreign nationals from seven designated countries for a period of 90 days. That ban/pause spawned litigation, and immediate losses for the President at the district court level, then a revised version of the ban (targeting only six countries) and new litigation. The original list of countries was: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Yemen. The revised order dropped Iraq from the list.

Two appellate courts in time upheld district court judges orders halting enforcement of the travel ban. But everyone knew the matter was headed to the Supreme Court, and SCOTUS has now issued its own compromise decision in the matter.

Six Justices joined in an opinion granting a stay to the lower court injunctions "in part." That is: the administration can for the time being enforce its travel ban against foreign nationals from the affected countries unless the travelers have "close familial" relationships with individuals in the United States, or can show a "formal, documented, and formed in the ordinary course" relationship to a U.S. institution such as a University. That's a fairly important qualification, but the Trump administration has been trumpeting this as an unambiguous win.

The Supreme Court has disbanded for its summer break, and the 90 days will run while the Justices are out and about their nine distinct lives. So it seems unlikely the SCOTUS will ever again address the merits of these particular executive orders. This per curiam opinion will have to suffice for the history books.

Personally, I'd like to see some numbers. I'm curious about the percentages. What share of the Iranian nationals (just to take one of the listed countries at random) who entered the U.S. in 2016 did so without any familiar relationship here, and/or any connection to an institution? Presumably some entered because they wanted to see the Grand Canyon or the Alamo, just as some from the U.S. travel to Iran in order to see the ruins of Persepolis or Amir Chakhmaq Square. I'm curious about the percentages, though.

Regulatory Takings

Finally, for today, regulatory takings. Murr v. Wisconsin.

I'm a great admirer of "regulatory takings" as a field of constitutional jurisprudence. The plain language of the fifth amendment says that private property not be "taken" for public use without just compensation. Now as a matter of common sense, of course a "taking" need not involve snatching the title documents away, or the equivalent. Regulations can take the value of the property and leave a shell-like title ownership. It took SCOTUS a long time to get around to acknowledging that, in Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council (1992).

In the subsequent quarter century, the court has been trying to get the kinks out of the new doctrinal vehicle. This was a case about one of those kinks. What is the "lot" for purposes of the application of the regulatory takings doctrine? The petitioners' parents purchased Lot E an Lot F separately in the 1960s. They transferred the two lots separately to the petitions in the 1990s (Lot F in 1994, Lot E in 1995). But the state takes the view that local ordinances effectively merged the lots, so that the petitioners no longer have a right to sell Lot E while retaining F.

SCOTUS has upheld that view. What is more important, the court has explained its decision to uphold the merger of E and F by virtue of a multi-factor analysis that will itself surely give rise to a thousand law review articles, a lot of billable hours for law firms active in the area, and unpredictable decision making going forward.

They didn't get a kink out. They worsened the kinkiness of the vehicle at this point.

Tomorrow

As I indicated in Thursday's post, tomorrow we look to human sexuality, that many-splendored source of litigation. If you dear reader won't stick around for a dose of sex, what would it take???

I'm a great admirer of "regulatory takings" as a field of constitutional jurisprudence. The plain language of the fifth amendment says that private property not be "taken" for public use without just compensation. Now as a matter of common sense, of course a "taking" need not involve snatching the title documents away, or the equivalent. Regulations can take the value of the property and leave a shell-like title ownership. It took SCOTUS a long time to get around to acknowledging that, in Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council (1992).

In the subsequent quarter century, the court has been trying to get the kinks out of the new doctrinal vehicle. This was a case about one of those kinks. What is the "lot" for purposes of the application of the regulatory takings doctrine? The petitioners' parents purchased Lot E an Lot F separately in the 1960s. They transferred the two lots separately to the petitions in the 1990s (Lot F in 1994, Lot E in 1995). But the state takes the view that local ordinances effectively merged the lots, so that the petitioners no longer have a right to sell Lot E while retaining F.

SCOTUS has upheld that view. What is more important, the court has explained its decision to uphold the merger of E and F by virtue of a multi-factor analysis that will itself surely give rise to a thousand law review articles, a lot of billable hours for law firms active in the area, and unpredictable decision making going forward.

They didn't get a kink out. They worsened the kinkiness of the vehicle at this point.

Tomorrow

As I indicated in Thursday's post, tomorrow we look to human sexuality, that many-splendored source of litigation. If you dear reader won't stick around for a dose of sex, what would it take???

Comments

Post a Comment